- HOME

- INVENTORY

- GALLERY

- BOOKS

- CATALOGS

- ABOUT & MORE

- CONTACT

Contact Us

Explanatory Marks:

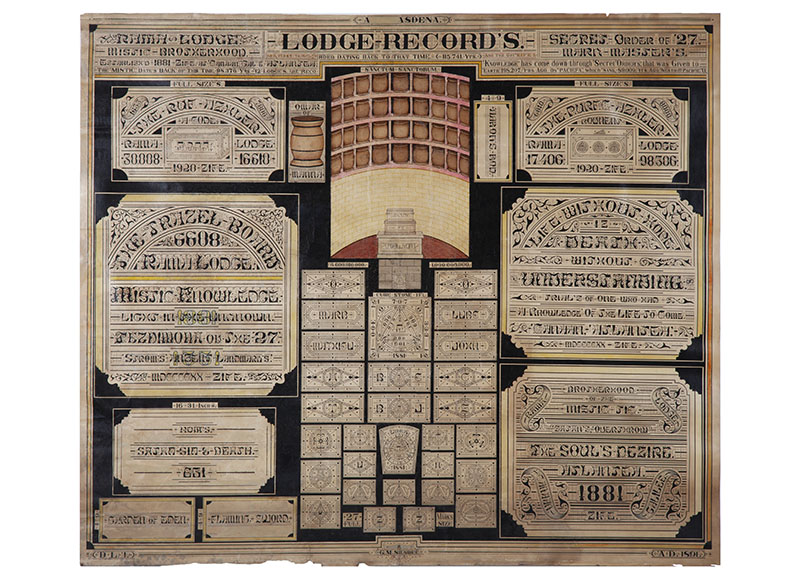

The Mystical Drawings of George M. Silsbee (1840 - 1900)Download PDF of catalog excerpt (click here). HIGH RESOLUTION IMAGES AVAILABLE.

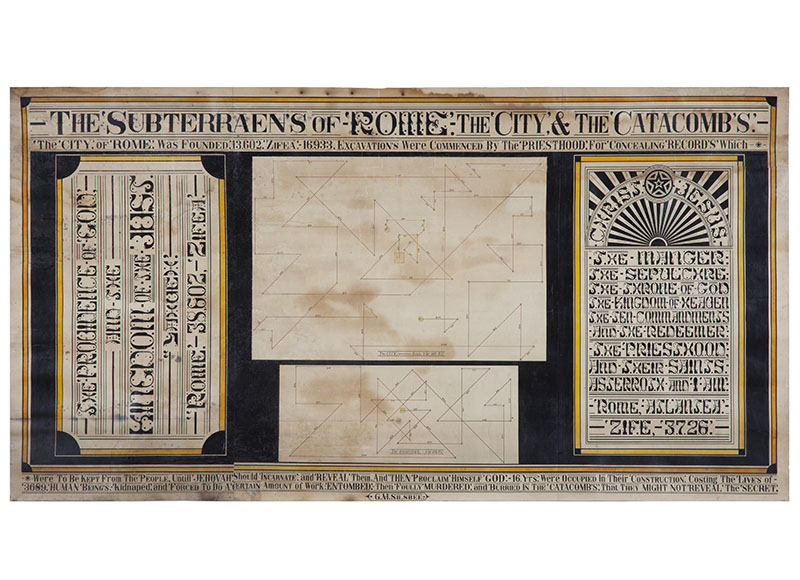

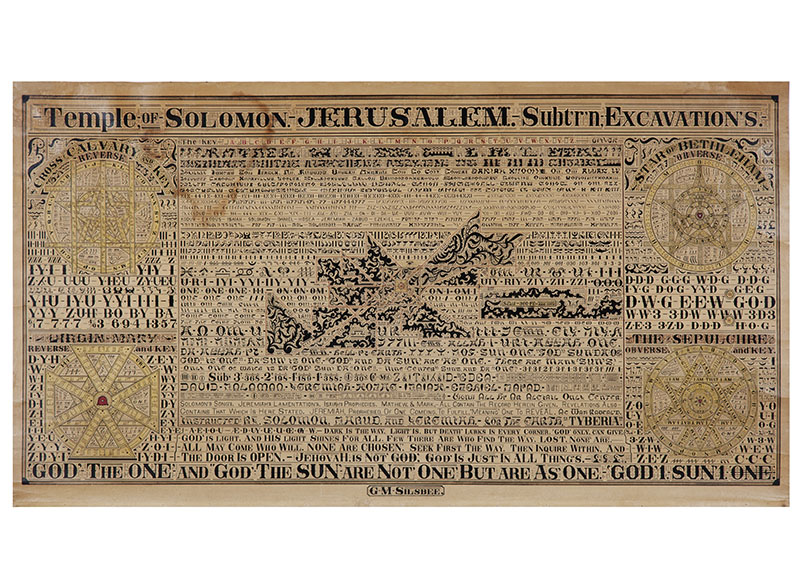

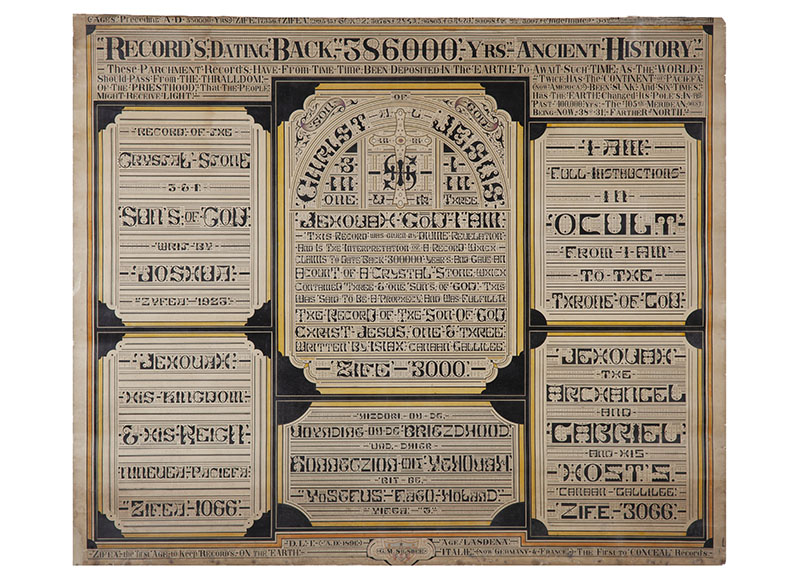

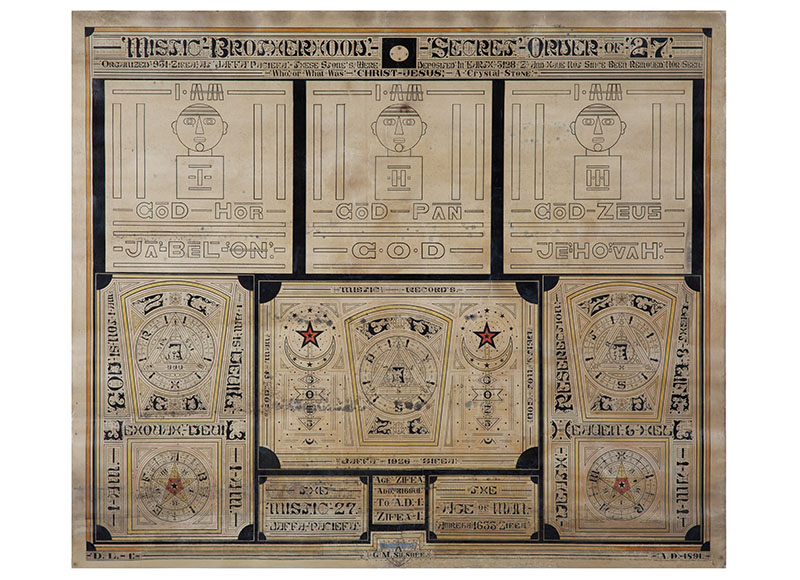

Steven S. Powers and Ricco/Maresca Gallery present, Explanatory Marks: The Mystical Drawings of George M. Silsbee. This collection of nine large-scale drawings, created in 1891, examine Freemasonry, Mysticism and the Occult. This sold out exhibit ran from January 28 - March 13, 2021.

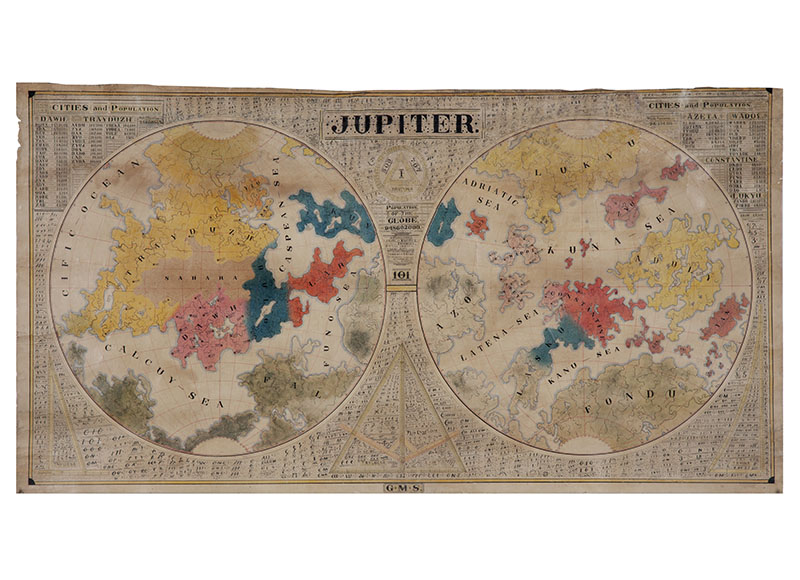

At different points during his life, George M. Silsbee was an artist, miner, engineer, and organ builder. But like many men in the second half of the 19th century, he also had a mystical alternate identity where ceremony, rites, and a mastery of secret symbolism connected him to something greater than himself. In his Masonic practice, he was a seer of rituals and conjurer of archaic wisdom, translating divine guidance into labyrinthine charts. Over a century since they were created, his works on paper—now exhibited to the public for the first time—offer a tantalizing vision to be untangled. Their dense networks of ink and watercolor calligraphy, encoded text, illustrations, and numbers—where no space for symbolism is wasted—suggest that with the right understanding one could journey through their protocols to ancient esoteric knowledge.

The known details of Silsbee’s biography, gleaned from census records, city directories, fraternal society publications, and newspaper archives provide just a spare sketch of the artist. Born on January 9, 1840, in Oneida County, New York, he died on his birthday in 1900 at the age of 60 near Waukau, Wisconsin. His obituary called him an “artist of ability”—although the medium of art is unspecified— and noted that he’d arrived in Wisconsin with his parents as a child in 1845 and later moved to Summit in Waukesha County. During the Civil War, he served three years in the First Wisconsin Cavalry and then in the 1870s relocated to Denver, Colorado. There he worked with organ builder Charles Anderson on an instrument with over 500 pipes, making it one of Colorado’s largest pipe organs. Then he moved on again, this time to the newly bustling Leadville, a major mining center of the Colorado Silver Boom, and spent two decades working as a miner and engineer.

In 1875, Silsbee was listed as a member of the Kenosha Masonic Lodge, No. 47 in Kenosha, Wisconsin, and it was during his years in Leadville that he embarked on the Masonic art that his family would call “his life’s work.” The mounting of the paper charts on linen with wooden dowels suggests they were meant to be unrolled and displayed, yet they were passed down in his family for four generations rather than being part of a Masonic lodge. Still, the square and compass that appear on a shield behind Silsbee’s signature on three of the charts—stonemason’s tools that are the most recognizable symbols of Freemasonry—affirm his work as that of a Masonic artist.

By the time Silsbee created these pieces at the end of the 19th century, the iconography and symbolism of fraternal societies had become largely standardized through the mass production of paraphernalia. Whereas the majority of fraternal society objects in the 18th century were crafted by local artists or were homemade, the huge boom in 19th-century membership led to a mail-order business for costumes, banners, décor, and anything else needed to turn a clubhouse in an ordinary American town into an occult temple to higher truths. While Christianity and the Bible were often at the center of these societies’ systems, they had an added theatricality through an appropriation of the ancient and “exotic” drawing in Victorian architectural and art movements ranging from Egyptomania to Moorish Revival. Silsbee’s experience as a Civil War veteran and worker in a rapidly industrializing society would have been akin to many of his fellow members who sought a community that was also an escape from modern life and its responsibilities.

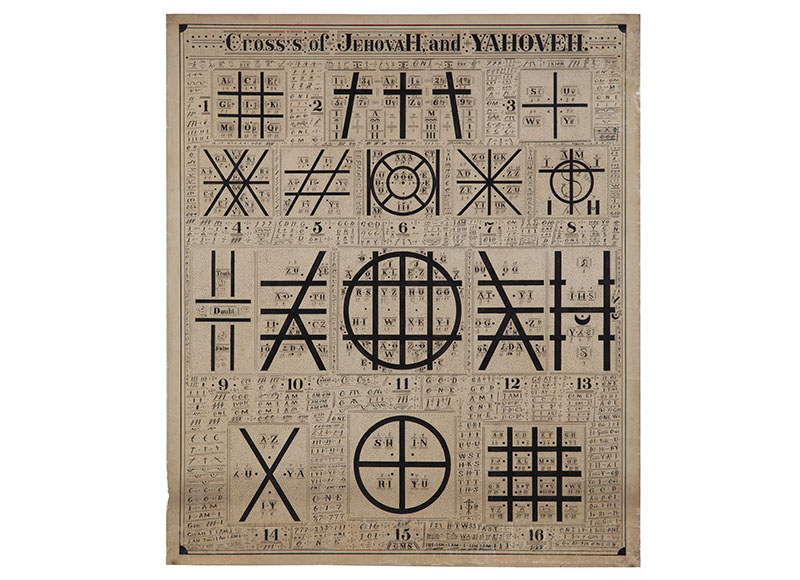

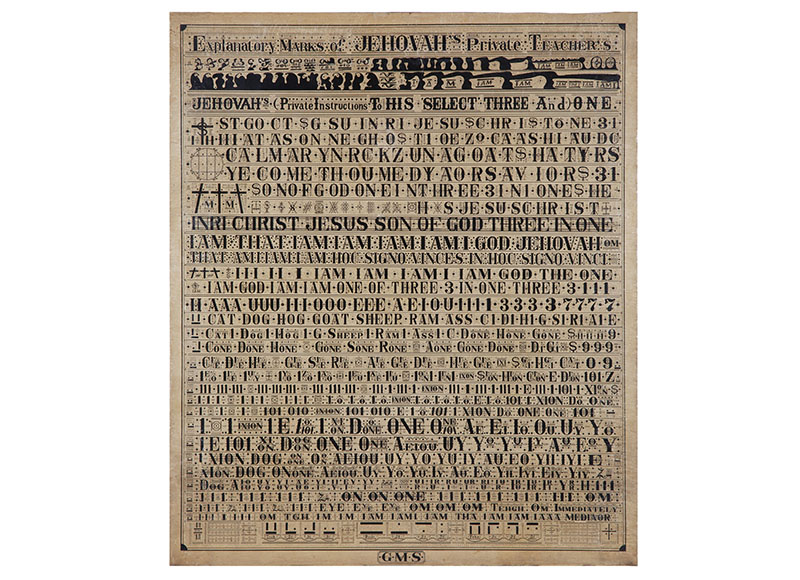

Silsbee’s work in its style stands apart from other Masonic art of the late 19th century. Degree charts and paintings were common in Masonic lodges, however, they tended to be figurative with allegorical scenes and vibrant symbols. Aside from a stylized map and an illustration of an inner sanctum, Silsbee’s charts are mainly ink on paper and only have a few figurative elements amid the stark typography and shapes. A small all-seeing eye overlooks a network of calligraphic flourishes; three abstracted faces stare out from the text announcing the names of the gods Jabulon (a uniquely Masonic term believed to represent a secret name of God), Pan, Zeus, and Jehovah, as if linking them all to one divine power.

In the cryptic text and symbols, his charts are more similar to Masonic ritual books than other forms of fraternal art. These publications were mnemonic aids for candidates learning the initiation ceremonies that would allow them to progress through degrees. To an outsider, the writing in these books looks like nonsense as its reading relied on an existing understanding of Masonic information, with the shorthand and symbolic prompts intended to help with memorization and personal study. Like Silsbee’s work, these books offered a way to ruminate on knowledge while upholding the candidate’s oath to “not write, print, paint, stamp, stain, cut, carve, hew, mark, or engrave” any Masonic secrets.

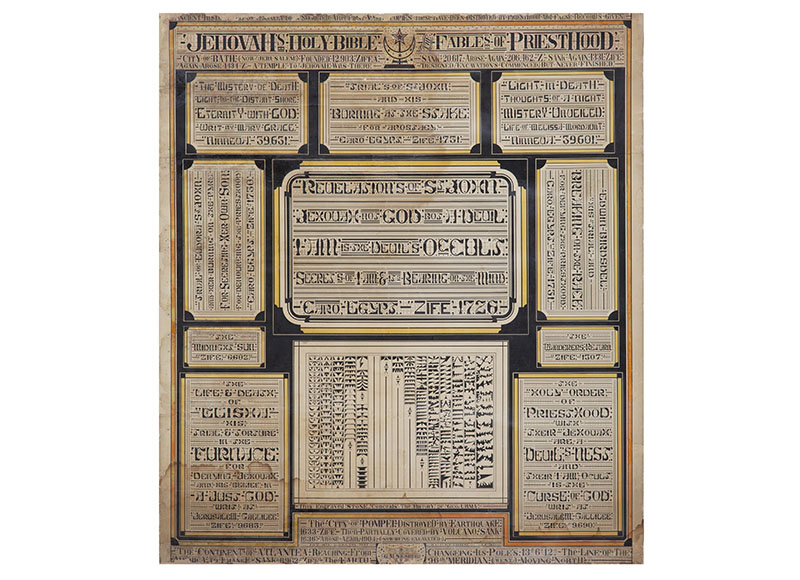

Examining each of Silsbee’s works is like focusing on something through a microscope, every approach revealing more and more detail that contributes to a greater comprehension of the whole. The incredible depth and variation of symbolism, from rune-like forms on the “Cross’s of Jehovah and Yahoveh” to the pigpen cipher key embedded at the top of “Temple of Solomon. Jerusalem. Subt’rn, Excavation’s,” show a deliberation where every mark is imbued with meaning. They include fragments of narratives referring to the Bible and the classical world, from records hidden in the Roman catacombs to the destruction of Pompeii, sometimes evoking subjects that would have been expressed in Masonic rituals, such as the “flaming sword” and its guardianship of the Garden of Eden that was frequently represented in Masonic lodges as a weapon with a wavy blade. Abstract patterns reminiscent of semaphore flags, signaling something to the viewer in their shapes that transform like an animation in parts, appear in a chart for “Jehovah’s ‘Holy Bible’,” while on “Temple of Solomon” the Star of Bethlehem is interpreted an otherworldly celestial presence with a lattice of intersecting lines, adorned with a rhythmic motif of dots and words.

Even without understanding the exact intentions behind each element of these works, it is easy to get pulled in by the repeating of phrases and characters that Silsbee used to build these pathways to knowledge of something ancient and spiritual. Moving through the scripts of “Explanatory Marks of Jehovah’s Private Teacher’s,” where black curls of ink and ciphers add to its aura of deep meaning, the phrase “I am” emerges again and again like a mantra: “Christ Jesus Son Of God Three In One I Am That I Am I Am I Am I Am I Am I God Jehovah ... I Am God I Am I Am One Of Three 3 In One.” It goes on and on, letters interrupted by numbers, symbols, and combinations that resemble equations. A textural pattern of tiny dots joins it all so you can almost hear the meditative tap of Silsbee’s hand reverberating through each line, trying to find a way to communicate sublime mysteries whose complexity could not be expressed by terrestrial images.

We are now witnessing these works far from their original context, not knowing the specific rite they were designed to guide, or the contemplation they were meant to inspire for those who understood the shared secrets. It is also possible we are only seeing part of a larger body of work that Silsbee created in his attempt to make the mystical into something navigable for those who were dedicated to learning. Now that Silsbee’s work has come to light, there is an opportunity to consider its intricacies as well as broaden the appreciation for the breadth of 19th-century fraternal art. Although it was likely made for clandestine purposes—to be engaged with by the select members of these groups—this art speaks to the human drive to connect with something sacred, to feel part of a long thread that through stories and rituals links us to the past. In these puzzles of symbols and words, much of Silsbee’s intentions remain enigmatic, but in exploring the obsessive patterns and ornate texts there is a powerful experience accessible to anyone who takes the time to look closely and let themselves be transported.—Allison C. Meier, 2020.

STEVEN S. POWERS • 53 STANTON ST, NY, NY 10002 • 917-518-0809 • email: steve@stevenspowers.com • © all rights reserved