- HOME

- INVENTORY

- GALLERY

- BOOKS

- CATALOGS

- ABOUT & MORE

- CONTACT

Contact Us

James W. Washington, Jr.: Stone Mason

***FOR WORKS AVAILABLE BY WASHINGTON, PLEASE GO TO THE OBJECTS & SCULPTURE PAGE***

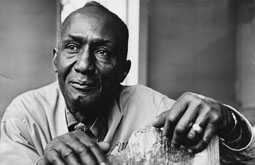

The son of an African American Baptist minister who was run out of town by the Ku Klux Klan and never to be seen again, and a deeply religious and supportive mother, James W. Washington, Jr. (1909-2000) knew from an early age that he had something unique within him—that his abilities and imagination would manifest and take him away from the segregated and oppressive environs of Gloster, Mississippi.

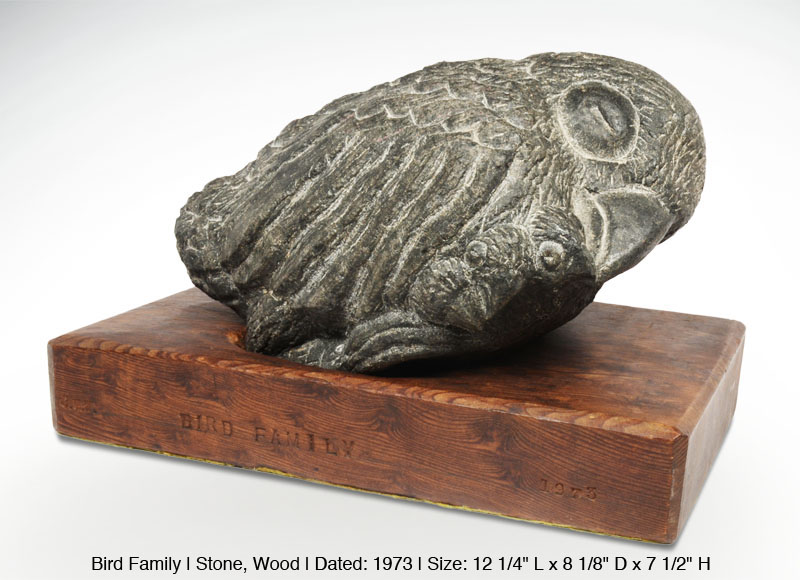

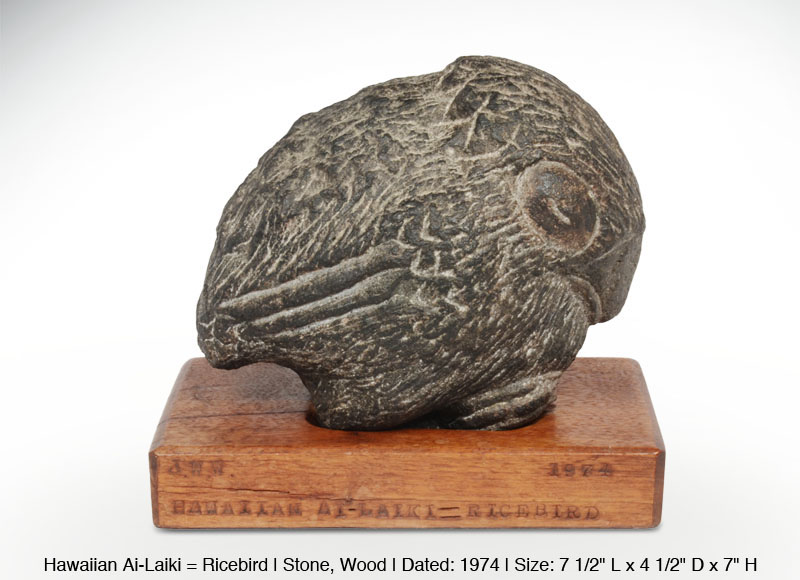

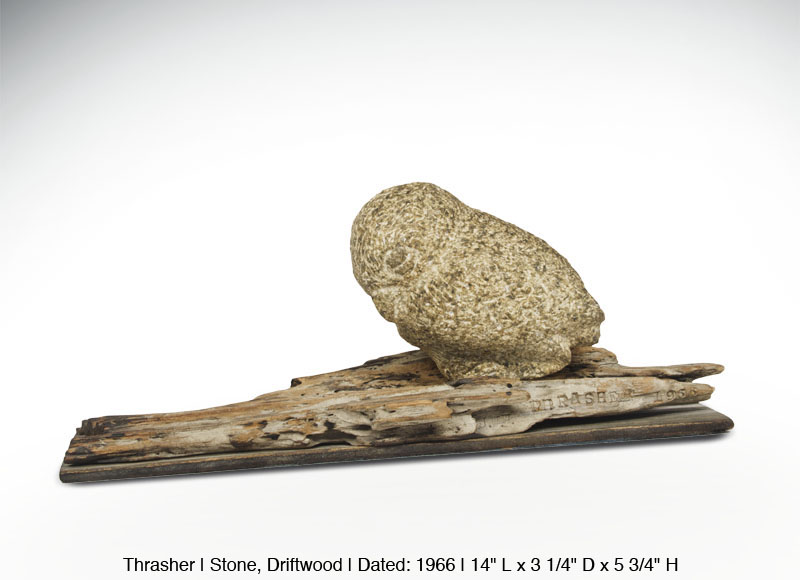

Washington’s spirited, but quiet carvings are often seen as a cross between two other direct carvers; the African American Folk Artist William Edmondson (1874-1951) and American sculptor John Flannagan (1895-1942). Washington felt that it was the spirit of God that he drove into stone to bring it to life. Edmondson thought his work was driven by the hand of God, while Flannagan felt that direct carving or taille directe, ensured vitality to the final carving. Improvisationalists know that something too studied may be proficiently academic, but often void of life. Therefore, Washington took right to the chisel—life starts with a spark—like a hammer’s first blow against granite!

From an early age, Washington displayed a sense of general inquisitiveness and proficiency for drawing. He remembered when he was thirteen or so, he would have friends make a random mark in crayon along the sidewalks and he would improvise upon it and “convert it into something alive and moving.” At seventeen years of age, it was through a government job with the Civil Service that Washington found his way out of Gloster and into Vicksburg, Little Rock, and then to the Seattle area in 1944 where he and his wife, Janie Rogella Washington, remained.

Along the way, while still working for the Civil Service, Washington developed his drawing and painting and became involved in the Works Progress Administration (WPA). In Vicksburg, in response to not being able to exhibit with white artists of the WPA, he organized and exhibited what he called “the first negro art exhibition sponsored by the WPA in the state of Mississippi.” Once in Seattle, Washington continued to paint and befriended Mark Tobey, with whom he studied for a time. Washington also organized exhibits and showed with Morris Graves, Kenneth Callahan, and Glen Alps.

Life changed for Washington in 1951, when he traveled to Mexico to meet with the muralist Diego Rivera. During that trip Washington explored the pyramids at Teotihuacan and was forever changed when he picked up (and took home) a volcanic rock that seemed to call to him. The rock lay in his studio for five years until he had a revelation and created, Young Boy From Athens. As Washington figured out those crayon marks along the sidewalks of Gloster, he figured out that Young Boy was within that volcanic rock. And the revelation hit hard! After, Washington declared, “I reached the conclusion that it was sculpting that I was supposed to do.”

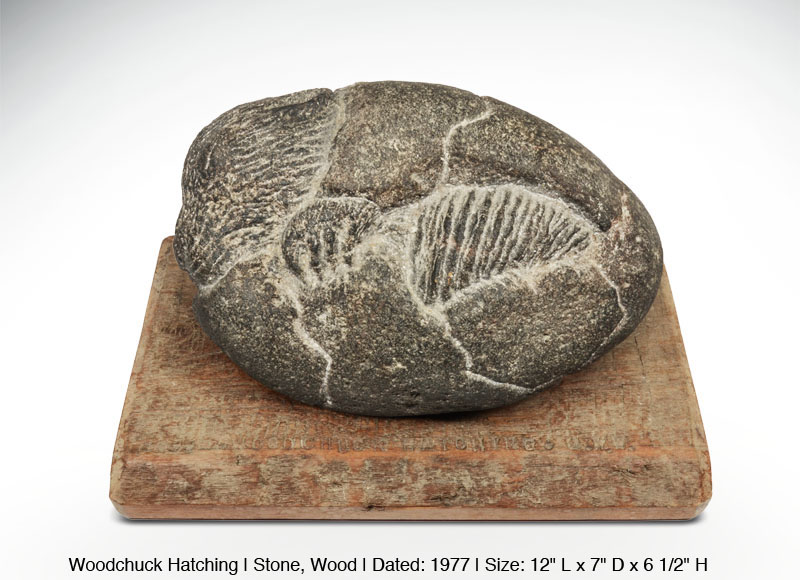

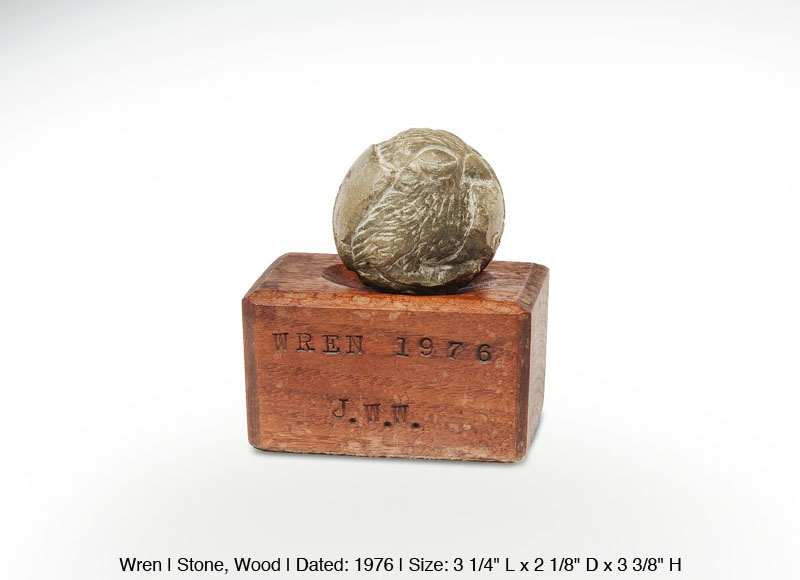

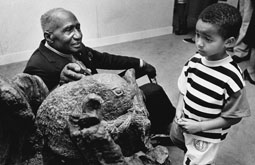

Washington taught himself to sculpt. He made his own tools and had no interest in traditional methods—he worked directly onto stones that inspired him. Life—genesis, growth, affirmation, fertility and freedom—was the single focus of Washington’s work. Washington would sculpt a bird hatching from an egg, or sperm chasing an egg, and sometimes, more playfully, he would carve a mammal being hatched from an egg (something that does not occur in nature). A patron, who upon seeing a recent work of Washington’s in which a rabbit was hatching from an egg, exclaimed, “A rabbit does not come from an egg!” Washington replied, “Doctor, all life comes from an egg.” He would also sometimes carve symbols from his practice of Freemasonry into his work (Washington was a 33rd degree Mason).

Paul Karlstrom (West Coast Regional Director Smithsonian Institution, Archives of American Art) wrote, "What is so impressive about artists such as Washington is the perfection with which fundamental humanism, generosity of spirit, and depth of emotion are embodied in their simple and humble forms. It is this quality that emanates from Washington's sculptures of birds and other small creatures. What sets them apart from a host of other animal sculptures is the inexplicable, yet undeniable, spirit in the stone."

Almost immediately after creating, Young Boy From Athens, and finding his true craft, Washington received numerous awards, accolades, purchases and commissions. He readily attracted the attention of many museums, galleries and the art patrons and philanthropists, John H. and Anne Gould Hauberg.

In 1989 the Bellevue Art Museum held a major retrospective entitled, "The Spirit in the Stone: The Visionary Art of James W. Washington, Jr." In 2008 for the inaugural exhibition of the Northwest African American Museum, Washington was honored along with Jacob Lawrence in "Making a Life, Creating a World: Jacob Lawrence and James W. Washington, Jr."

James W. Washington, Jr.'s work is represented in numerous private and public collections, including The Smithsonian, The Whitney, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and the Seattle Art Museum.

Selected sources: Paul Karlstrom, The Spirit in the Stone: The Visionary Art of James W. Washington, Jr., Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1989; Regina Hackett, "James Washington: Secrets in Stone," American Artist, November 1977; Deloris Tarzan Ament, Iridescent Light: The Emergence of Northwest Art, Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2002; Romare Bearden & Harry Henderson, A History of African-American Artists: From 1792 to the Present, New York, Pantheon Books, 1993.

STEVEN S. POWERS • 53 STANTON ST, NY, NY 10002 • 917-518-0809 • email: steve@stevenspowers.com • © all rights reserved